Victorian Memento-mori & the Art of Taxidermy

Among the Victorians, death was a frequent visitor and they had an overwhelming tendency to commemorate the death of a loved one, even family pets were immortalised in death.

The introduction of the daguerreotype, the first commercially exploitable photographic process in 1839, provided an important new way for the bereaved to remember their dearly departed. It was customary to photograph the deceased posed in a natural position to appear sleeping. Sometimes the dead were propped up in a standing or sitting pose creating an impression of a living subject. This nineteenth century popular trend - pictures that portray the dead as living - occasionally featured the deceased posed next to living family members.

It is unfortunate that Post-mortem photography is often misinterpreted or misunderstood by the modern-day viewer. Far from being a morbid fascination with the macabre, Victorian images of death and mourning were "treasured mementos" that permitted the bereaved to capture the serenity of death, providing a lasting remembrance to celebrate a loved one's life and preserve their memory. Their function was to help mourners acknowledge their loss and embrace life.

By the mid 1860s, a popular format was the card-mounted photograph or Carte-de-Visite, succeeded by the notably larger Cabinet Card. One could order countless copies, which made them ideal to be mailed to friends and relatives. The simplicity of these photographs makes for powerful imagery, a kind of ‘Tableau Vivant’, providing final visual record for posterity.

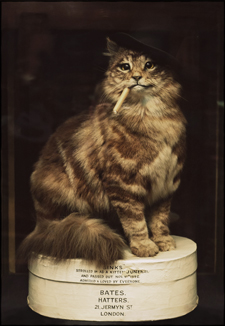

The medium of taxidermy creates similar references to postmortem images, as the intention is to give us the illusion of life in death, ensuring the animals survival through their artificial afterlife.

For Victorians, the nineteenth century was an age of exploration and saw an upsurge of interest in the natural world. As naturalists brought back wondrous natural curiosities from the far reaches of the colonial world and beyond, many people developed a fascination with animals and plants from home and foreign lands.

In the absence of other adequate means of preserving the details of all these products of nature, taxidermy reached new heights of popularity. Taxidermy shops became important meeting places, not only for naturalists and sportsmen, but also, where the mainstream interested in natural history sought out and exchanged information, and encountered new or rare specimens. The taxidermist's output served a partly scientific purpose; in addition, much of it emerged as a key element in interior decoration, and curiously also for the adornment of ladies' hats. The preservation of a deceased family pet was another popular trend of the period. Most often dogs, and occasionally other beloved pets and heroic animals were transformed into a lasting memorial for posterity.

Victorian sensibilities and aesthetic took the preparation and display of preserved animals to a new level of naturalism by combining art and science, with it came a new way of seeing and thinking about the natural world. Taxidermists were mounting specimens in theatrical poses for display at international exhibits and natural history museums had discovered the didactic value of taxidermy. Subsequently, museums adopted the trend toward naturalistic display that emphasized narrative by placing groups of animals in a simulated natural environmental stage-set. Habitat dioramas were designed to create illusions of wilderness, apparently free from human interference. The use of animal skin and parts in the construction of these man-made bodies contributes to the notion of authenticity. Its hyper-realistic features may unsettle, provoke or enthral the viewer, but moreover, provide the opportunity to engage in the social and cultural context of their making.

Human ideas and concepts are significantly shaped and redefined in response to culture, values, and ideology. Museums throughout the world have undergone many major changes in an attempt to suit 'contemporary' sensibilities and ethical positions in relation to conservation and the treatment of animals. In due course the use of taxidermy was considered to be unnecessary and old fashioned. As a result many habitat dioramas have been dismantled and mounts removed from public display to storage and, in some cases, so-called ‘old stuffed specimens’ have been destroyed.

While, taxidermy art is popular once more in the 21st century, and remains an important tool in education and conservation, it is still a controversial subject.

Today still not all intricacies of the history of natural sciences are understood and therefore appreciated and certainly the use of post-mortem photography and taxidermy are no exception.

Studying and immersing oneself in the socio-cultural fabric that saw the birth and creation of these artifacts provides a rich and complex context for a better understanding of this unique subject and its extraordinary place in history.